Choice Fields

Intro

This is a part of a series of articles that will attempt to explain how I think when I design – my system, in a way. I’ve somewhat arbitrarily nicknamed it Trinity, and hopefully by the end of the series I’ll be able to explain why I picked that name. The purpose of these articles is not to create a formula, to create a rigid system, or even to suggest that my system is better than another.

The whole purpose is just to try to explain, in writing, how I think when I design games.

Important points from the last article

In the previous article (Link to Part 1), we went over two important principles:

The Big Principle: A game is fundamentally a conversation between the designer and the player.

Principle #1: As a game designer, your job is to ask your players questions. The players’ job is to answer those questions using the tools you give them.

A Disclaimer

At the end of the previous article, I mentioned a concept I call “choice fields.” In this article, I’m going to attempt to explain these to you, but I have to say this first:

The subject is really complex, and I’m probably not going to be able to explain every facet in one article.

“Emergence”

In order to understand what a Choice Field is for, first I need to explain a decade-old concept: Emergence.

In 2002-ish, after Grand Theft Auto 3 (GTA3), the most popular buzzword in the video game business was “emergence,” often in the context of “emergent gameplay.” The term was coined mainly to describe the kind of open-world, “sandbox-y” gameplay that GTA3 was the first to really do well.

The term got its name from the way brand new gameplay objectives seemed to “emerge” from the overlapping of small sets of rules and abilities. Play styles that are not part of the game objectives seemed to come out of nowhere, and players found themselves spending tons of time creating goals in the game world for themselves and spending more time doing those than actually finishing the critical path missions.

Choice Fields

In thinking about how to design Emergence into a game, we can’t think about what kinds of things we “want” to emerge (because then we’re just designing them into the game). Instead, we need to think about how to create the overlapping sets of rules and abilities (questions and answers) that create the environment from which emergence springs. That overlapping set of rules and abilities is what I refer to as a Choice Field. More specifically, though:

Choice fields are a collection of spectrums all of which describe a single game mechanic.

Game Mechanics

Basically a game mechanic is any arbitrary set of “things” in your game. If you can imagine being assigned to work on a thing by your boss, it’s probably a game mechanic. I’m using the term “Game Mechanic” here in an odd way on purpose – since I’m not really looking to get too specific in to what’s inside a game mechanic yet.

Example Game Mechanics: An enemy, the player, the level design, the metagame design, the vehicle system…

You’ll notice that mechanics can contain other mechanics. This is cool. I really just need a word so I don’t have to keep typing “that thing the choice fields are connected to” over and over again.

Spectrums

“Spectrum” here refers to any two “opposite” concepts which are the same in nature, but differ in degree.

For example, long and short are both measurements of “range” (their nature) but completely opposite in degree.

Examples of spectrums:

- High / Low (Health)

- Long / Short (Range)

- Cheap / Expensive (Cost)

- Fast / Slow (Speed)

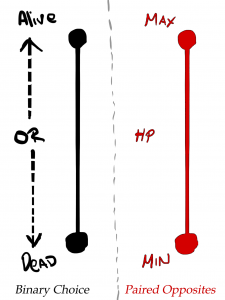

I want to differentiate spectrums from “binary choices.”

Binary choices are two opposites that differ in nature, but are the same in degree.

Examples of binary choices (generally avoid these in Choice Fields)

- Left/Right

- Yes/No

- Right/Wrong

Binary choices are less useful than spectrums and produce much more limited results. You only get all of one or all of the other. They do not define a spectrum, but rather a fork.

When working with Choice Fields, binary choices are useful in certain rare situations, but should generally be avoided.

“Dimensions”

Each individual set of spectrums in a choice field is called a “dimension.” Choice fields can have any number of dimensions, but they generally have between one and three.

I’m not even going to try to explain this without pictures, so I’m going to go through examples of the first three dimensions below, and hope you get the idea.

Choice Field Examples

1-Dimensional Choice Fields

The simplest choice field is a “one-dimensional” field. Basically it means it only contains a single spectrum or a single binary choice. (This is one exception to the “no binary choice” rule of thumb I mentioned above.)

As an example, let’s take the mechanic “Enemy” and the mechanic “Player” and attach a single binary choice to each one:

- Game Mechanic: Enemy

- Binary Choice: Alive or Dead

- Game Mechanic: Player

- Binary Choice: Alive or Dead

Let’s pretend these two resultant choice fields are the only ones in the whole game: An Enemy that kills a Player in one hit, and a Player that can kill an Enemy in one hit.

The game designer is asking the question: “Do you want to attack this enemy or not?” The Player has an ability that allows it to kill an enemy.

Note: This doesn’t get much more interesting if you substitute spectrums for the binary choices.

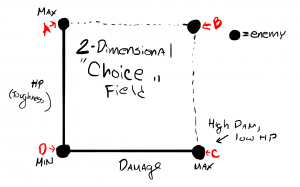

2-Dimensional Choice Fields

One-dimensional choice fields aren’t super interesting most of the time, so you don’t see them used a lot. More often you’ll see two-dimensional Choice Fields.

In a two-dimensional choice field, you take two spectrums and splice them together. This is much easier to see than to describe.

Using the same example as above, you end up with a choice field that looks something like this:

- Game Mechanic: Enemy

- Spectrum #1: Min HP to Max HP

- Spectrum #2: Min Damage to Max Damage

Each dot on the diagram represents an Enemy that is an example of the extremes we’ve built into this Choice Field.

- Max HP, Min Damage – “Defender”

- Max HP, Max Damage – “Heavy”

- Min HP, Max Damage – “Attacker”

- Min HP, Min Damage – “Swarmer”

The designer is now asking the question, “Which of these Enemies do you want to attack first,” and the Player must be supplied with abilities (Weapons) to deal with all four Enemies created by this diagram.

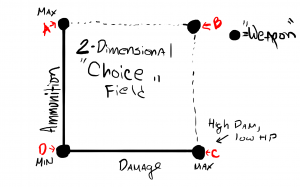

The choice field for the player’s Weapon mechanic might look something like this:

Each dot on the diagram represents a Weapon that is an example of the extremes we’ve built into this Choice Field

- Game Mechanic: Weapon

- Spectrum #1: Min Ammo to Max Ammo

- Spectrum #2: Min Damage to Max Damage

EXAMPLES: (Ammo is represented in these examples as “breakability” – number of times it can be used before it breaks)

- Max Ammo, Min Damage – “Whiffleball Bat”

- Max Ammo, Max Damage – “Sword”

- Min Ammo, Max Damage – “Chainsaw”

- Min Ammo, Min Damage – “Fragile Stick”

So if we assume these two Choice Fields are the only ones in the game, our game now looks like this: We have four Enemies, each of which has different health and damage values. The player has access to four Weapons (A, B, C, and D), each of which has different damage and ammunition values.

The player will want to use a high-damage weapon to kill a high-hit point enemy and vice-versa. The addition of the ammunition spectrum makes sure that you can’t use every weapon all the time, and keeps them in balance with the Enemy choice field.

You can see how the Enemy and the Player develop their choice fields in parallel. This is done deliberately. You can start with either, but they are both dependent on each other.

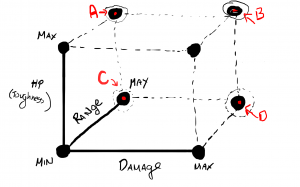

3-Dimensional Choice Fields

There are a lot of times where a two-dimensional choice field is exactly what you want (I’ll hopefully get into that in later articles), but often you’ll want things to be a bit deeper.

I’m imagining that most of you read the description of the game assembled in the previous section and thought something was missing, or felt imbalanced. What was missing is a third dimension. I’ll get right into examples.

Let’s take the Enemy mechanic from the previous example and add another dimension to it: Range.

- Game Mechanic: Enemy

- Spectrum #1: Min HP to Max HP

- Spectrum #2: Min Damage to Max Damage

- Spectrum #3: Min Range to Max Range

You can see that adding this one dimension once again doubled the number of dots in the diagram. As before, each dot is an example of the extremes we’ve built into this Choice Field. We get four new Enemies out of this (A, B, C, and D) which are the same as the enemies from our two-dimensional example but with the ability to strike at range:

- Max HP, Min Damage – “Defender”

- Max HP, Max Damage – “Heavy”

- Min HP, Max Damage – “Attacker”

- Min HP, Min Damage – “Swarmer”

Again the game would be asking, “Which enemy do you want to attack?” The player would need the ability to deal with Enemies at range, so now there are four more possible weapons in our Weapons mechanic, each capable of striking at range:

- Max Ammo, Min Damage – “Shotgun”

- Max Ammo, Max Damage – “Gatling Gun”

- Min Ammo, Max Damage – “Sniper Rifle

- Min Ammo, Min Damage – “Pistol”

You can see how adding just that one dimension to each of our Choice Fields immediately enriched the available options we have for designing challenges for the player.

Caveat

Just because there’s a dot in a diagram above, doesn’t mean it’s a good idea to use it. I’ve found the sweet spot is to make a three-dimensional choice field, like examples above, and only use 3-4 of the 8 dots in it at a time (e.g. 3 enemy types per level). You get lots of variety without overwhelming the player with complexity. I’ll explain more in later parts of this series, how I choose which “dots” to keep for a given section of a game.

Next Time

Next time I’m planning to go further into Choice Fields, and hopefully show how you can build a workable game mechanic design up from just a few of these.

Also, this article is waaaay too long. If I come across another subject this weighty, I’m going to have to break that article into two parts. It’s just too much to handle in a week.

Patreon Credits

(http://www.patreon.com/mikedodgerstout)

Champions

Petrov Neutrino

Guardians

Martin Ka’ai Cluney

Patrons

Vincent Baker

Teal Bald

Jesse Pattinson

Benefactors

Annie Mitsoda

Katie Streifel

Mad Jack McMad

Nikhil Suresh

Supporters

TheYuanxian

Oliver Linton

Jason VandenBerghe

Backers

Mary Stout

Kim Acuff Pittman

Matt Juskelis

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.